You don’t hear much about plasma TVs these days, and for good reason: no one’s made them for several years. But for a TV technology that was once the pinnacle of picture quality, where did plasma TVs go?

Writing about a much-loved technology that’s been and gone feels like writing a love letter to an ex. You remember the reasons you loved them, and you also remember how they annoyed you. It’s a soul-cleansing exercise.

But what do we recall when we talk about plasma TVs? The technology that made flat screens an everyday reality for you and I originated in a humble lab in the University of Illinois. The potential of what started as an academic experiment to create a display for educational computers became very apparent to TV manufacturers, which had been struggling to find a realistic solution to take over from cumbersome CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) TV sets.

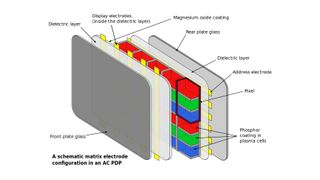

Plasma screens feature millions of cells, filled with gas, sitting neatly between two sheets of glass. When they’re charged with electricity, the cells – or pixels – lit up to form the image. That charged-up gas is called plasma, hence the name of the screens.

CRT models, on the other hand, feature a single tube that defines the size of the screen. The move to plasma technology and its use of millions of cells made it far easier to enlarge screen sizes, while also making them thin – far more slender than normal CRT sets. In addition, the higher definition and refresh rate resulted in a much higher-quality picture.

To understand the lure of plasma and how it managed to conquer hearts and living rooms alike, you must look beyond the pretty screen and deep into the heart of the technology behind it.

- Next-gen TVs: the OLED, Micro LED and holographic TVs of the future

Plasma TVs: how do they actually work?

Think of a plasma TV as a neon lamp. It’s built on an emissive technology that uses plasma to excite phosphors to emit light.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

“The glass is comparable to window glass, unlike LCD. There are horizontal and vertical electrode grids and a phosphor array. The connection between the two is scanned, firing the discharge at the intersection and causing the phosphor to glow,” says analyst Paul Gray, who leads TV research at Omdia, a global firm that provides analysis across the technology ecosystem. “The phosphor side is similar to CRT, while the plasma is a glow discharge like a neon lamp.”

But the genesis of the technology had nothing to do with the entertainment industry. Larry F Weber, a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers wrote the following in IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science:

“As with any invention, it all started with a need. In this case, it was the need for a high-quality display for computer-based education. The University of Illinois started a project in 1960 called PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations) to conduct research on the use of computers for education… The plasma display panel (PDP) was invented by Prof. Donald L Bitzer, Prof. H Gene Slottow, and their graduate student Robert H Wilson in 1964 to meet the need for a full graphics display for the PLATO system.”

The technology evolved fast – literally from lab glassware to the best TV screens – in a very short space of time.

Plasma TVs: the early days

However, as would be the case with any technology product for the consumer market, there was a long period of low-volume but high-cost production.

The first manufacturer to take the dive into making plasma in serious numbers was Fujitsu, making a 42-inch screen in 1997. That screen was selling for $20,000 (around £15,000 / AU$26,000), according to San Francisco Business Times.

Philips and Pioneer followed suit, and other manufacturers piled in shortly afterwards.

“The starters were Fujitsu and Panasonic, but NEC, Pioneer, Samsung, LGE and Chunghwa (CPT) all made the displays,” says Gray. “Most brands had plasma in their ranges. It’s important to remember that in the early 2000s, the PDP [Plasma Display Panel] was in the lead in large-screen TVs such as 42-inch models, and there was serious concern whether 42-inch LCD was economically feasible. Sony and Sharp even worked on a hybrid technology called PALC, Plasma-addressed Liquid Crystal.”

It was the first time that a large TV was available in a form that could be mounted on a wall. This was a huge leap forward from the furniture-piece CRT TV sets that were boxy and heavy, although sturdy. Remember, also, that it was a strange world where small screens and large screens (LCD and projection respectively) were flat, but the ones in the middle (14-inch to 37-inch) were curved.

Plasma TVs: picture quality

Plasma TVs had come a long way since its first iteration. It went on to dominate the consumer market for TV screens and provided one of the best viewing experiences available.

Plasma TVs had panels that lit up small cells of gases (xenon and neon) between two plates of glass, offering very bright and crisp images even on a large screen surface, according to Samsung, which was one of the main manufacturers of plasma TVs. The screens contain phosphors that created the image on the screen light up themselves and don’t require backlighting.

The technology meant that large screens (typically from 42 inches to 63 inches) “offer high contrast ratios, gorgeously saturated colours, and allow for wide viewing angles – meaning every seat in the house is a great one,” according to Samsung, while it worked “well in dimly lit rooms, which is great for watching movies.” It could also “track fast-moving images without motion blur,” making plasma “ideal for watching action-packed sports or playing video games. The sharpness of visual detail is astonishing.”

However, there were some disadvantages. Plasma was more of an electricity guzzler than LCD (Panasonic had got the consumption pretty much to parity, and plasma’s power consumption depended heavily on the amount of light in the video content). It was heavier, with many more power electronics packed in each set. It wasn’t as bright, meaning that to enjoy it fully, you really needed to like your dimly lit, cinema-style watching experience – which wasn’t a disadvantage if you weren’t a fan of daytime telly. Burn-in was an issue, too, especially for avid gamers.

The plasma boom and the new kids on the block

By 2005, six million units of plasma were being shipped globally per year, according to Omdia’s data. “The business peaked at 18.4 million in 2010,” says Gray.

But then other technologies started to catch up. LCD screens were lighter and brighter. They consumed far less energy and performed better in daylight.

“Essentially, the fundamental problem was the pace of innovation,” says Gray. “Plasma needed to counter the LCD industry, which had more players working on development. It faced either an uneconomic level of R&D or, alternatively, slowly falling behind. Samsung and LG were only in the PDP [Plasma Display Panel] market as an insurance policy, while the Japanese were unwilling to make big bets. In fairness, they acted rationally – while Korea Inc got its money back in LCD, Taiwan Inc only broke even and China Inc’s chances of ever making a positive return on its LCD investment are slim.”

The end of plasma TVs

The plasma honeymoon didn’t last, then, and there were some basic factors that had a severe impact on sales – including one of the criticisms commonly levelled at OLED, being low brightness.

“Plasma wasn’t as bright as LCD. Critically in US retailers, the TV area was brightly lit and PDP looked washed out,” says Gray. “Plasma – like all emissive displays – struggled with fine pixel densities. Only Panasonic managed to make a 1080p 42-inch, and even then it wasn’t a great product commercially. Manufacturing yield was reportedly poor. In the end, LCD had massive manufacturing capacity and the advantage of scale. PDP simply wasn’t unique enough.”

As manufacturers started making huge losses, they began to phase out plasma. Pioneer putting an end to the production of its much-loved Kuro screens was notable. When Panasonic announced that it would no longer make plasma screens, everybody knew that the end was near. LG and Samsung followed suit shortly after. And just like that, the light went out on plasma.

- What is OLED? The TV panel tech explained