How 3D printing could pose a threat to your privacy

Watermarks in 3D printed objects have the potential to reveal private information

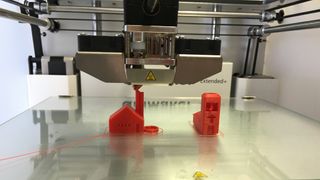

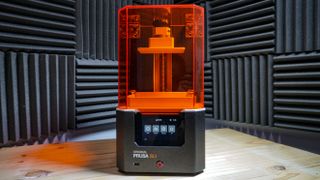

3D printing was first employed as a fast and inexpensive way to create prototypes before manufacturing. However, in the past few years, 3D printers have become significantly cheaper and more readily available to the average consumer. These days, users around the world are taking advantage of 3D printers to create all kinds of different objects which can be purchased online or printed yourself if you have the necessary equipment and materials.

While 3D printing has tremendous potential when it comes to being able to create objects at home without the need to travel to a store, the technology could also pose a “grave and growing threat” to individual privacy due to the potential for 3D printed objects to reveal private information about individuals. TechRadar Pro spoke with Dr. James Griffin from the University of Exeter and Dr Annika Jones from Durham University to learn more about their research on the potential privacy threats posed by 3D printing.

- We've put together a list of the best 3D modeling software around

- These are the best all-in-one printers on the market

- Also check out our roundup of the best portable printers

How has 3D printing evolved over the last few years and how close is the technology to mainstream adoption?

3D printing has evolved exponentially, and is now reaching a stage where we can see people starting to use it in everyday activities. The mainstream technologies could still be criticised for being a bit basic, but extremely capable printers are dropping in price all the time. Don’t be surprised if within the next ten years, you have a fast 3D printer capable of printing complicated metal and plastic objects in your garage (and this time, it isn’t just hyperbole!)

Why does 3D printing pose a threat to individual privacy and could it be more invasive to user privacy than the Internet of Things (IoT)?

3D printing doesn’t per se pose a threat to privacy (although we have heard [unsubstantiated] rumours of printers passing information about prints back to manufacturers). The issue we have raised is in the use of watermarks to reveal information about the activities of users. For example, a watermark embedded onto a 3D printed object could be tracked and traced through photographs online, e.g. through google image search. If this were, say, a piece of jewellery, it might be a way to track the movements of an individual; likewise, some 3DP implants could be traced through the use of x ray equipment. The files themselves could also be searched for online. The possibilities are, ultimately, endless.

Similar technologies can be employed by the IoT, indeed, there is some overlap. However, the interesting thing about 3D watermarks is that they could be on an analogue physical object, and they can be different for every single print. In effect, it could allow for a blockchain or Google search for physical objects – imagine that! As the IoT becomes more predominant, then these devices could recognise 3DP watermarks, in effect bringing together the 3DP analogue world and the digital world. If, as one would expect, 3DP becomes mainstream in the future, then we can see that the use of 3DP watermarks in conjunction with IoT could become rather common and a critical component in our everyday lives.

How can the origins of 3D printed objects be traced and would this be easy to do without technical knowledge?

Right now this is not so easy, but I am sure this will quickly change. There is a market incentive to implement watermarks into 3D prints – e.g. to find out how consumers use 3DP objects, in exactly the same way that online content providers use watermarks to know how their content is being used.

In summary - watermarks might assist governments in surveillance; they can assist companies to find out what consumers want; they could enable an individual to spy on another. We argue that we should be wary of some of the uses to which watermarks could be put.

However, there are some extremely beneficial uses. One which is becoming apparent through our research is that watermarks can be used in medical devices. They could be used in ensuring the quality of the source materials, and they can be used to ensure the continued stability of a print (e.g. 3D printed organs etc).

Can you tell us a bit more about the 30 in-depth interviews you conducted with representatives from Chinese 3D printing companies?

We had funding from the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Newton Fund and the Ningbo Science and Technology Bureau to carry out these interviews in China. This was achieved through the University of Nottingham’s Ningbo campus. We interviewed companies mainly in Shanghai and Beijing. Separately to this research, I have spoken to similar companies in the UK and the parallels in the concerns and issues raised was striking.

Are watermarking technologies currently being used in schematics for 3D printed objects uploaded to platforms such as Thingiverse?

Not to my knowledge, but watermarks can be platform agnostic. You could put a watermark into any file, without the knowledge of the platform. Platforms could take advantage of a watermark (e.g. for licensing purposes) if they so wish though.

What kind of regulations do you think should be put in place to protect the privacy of users when it comes to 3D printing?

Our main concern is to raise the issue. It would be great if regulation could be achieved without government intervention, but it might become necessary if these privacy issues become significant – which we think they could do, very quickly. Given the global nature of the Internet, it would be useful to have some guidance at international level, e.g. in a voluntary code which would be associated with a kitemark. The trouble with our current law is that there is protection (probably!) available for digital watermarks for copyright works, but that protection does not take into account privacy concerns. Indeed, it could be making matters worse by protecting privacy invading technologies. Similarly, the scope of the current law is likely to only cover copyright works, and not the more beneficial uses of watermarks in e.g. bioprinted technologies.

- We've also highlighted the best 3D printer

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!